What You’ll Learn From This Report

Introduction

In 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom stood beside Carolina Ledesma at her property in dusty Tombstone Territory, an unincorporated neighborhood southeast of Fresno in California’s Central Valley. He was there to sign SB 200, a measure he claimed would direct funding to people in dire need of water after their wells dried up. 1California Senate Bill No. 200. Legislative Counsel’s Digest. Passed July 24, 2019.

Last month, Chirag G Bhakta, Food & Water Watch’s California Director, visited her house, accompanied by Mariana Alvarenga from the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability (LCJA) and FWW colleague Jessica Gable. Carolina’s well is still dry. Fragile persimmon trees bake under a relentless sun, and yet Carolina offers us the best of her fruit. We wash the persimmons in her outside sink, the steady trickle of water from tanks shipped in by state authorities. But it becomes clear that this small supply of water is only a temporary solution to the dire water shortages in Tombstone Territory.

Only blocks away from Carolina’s neighborhood, lush green orchards thrive. Irrigated by wells drilled deep into the earth to collect increasingly precious groundwater, these nut farms are living illustrations of the historic inequities etched into California’s water policy.

Across the state, groundwater resources account for 30 percent of water used by California agriculture in wet years, and for a staggering 80 percent of water in dry years.2Bernacchi, Leigh A. et al. “A glass half empty: Limited voices, limited groundwater security for California.” Science of the Total Environment. Vol. 738. May 2020 at 2. In the San Joaquin Valley, farms suck up an estimated 89 percent of water used by the region — compared to the 4 percent used by the valley’s residents.3Hanak, Ellen et al. Public Policy Institute of California. “Water Stress and a Changing San Joaquin Valley.” March 2017 at 16. And despite years of drought and dry conditions, thirsty almond acreage across California expanded by 78 percent between 2010 and 2022.4U. S. Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. “2021 California Almond Acreage Report.” April 28, 2022 at 8. Meanwhile, the climate crisis is intensifying prolonged drought conditions in California and across the American West. California is currently experiencing the driest 22-year period in more than 1,200 years.5Williams, A. Park et al. “Rapid intensification of emerging southwestern North American mega-drought in 2020-2021.” Nature Climate Change. Vol. 12, No. 3. February 2022 at 1. Record drought and years of poor water management means that the pain of California’s water crisis is felt acutely by rural households with domestic groundwater wells in the Central Valley. In Tombstone Territory, despite numerous studies, reports, and plans, wells are still dry, and agriculture is still expanding and sucking up groundwater.

In 2012, Governor Jerry Brown signed FWW-endorsed legislation6CA A.B. 685 (2012). that made California the first U.S. state to recognize the human right to water. That bill established that “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes,” and that all California policy must consider this right when establishing new policy or regulations.7California Water Code § 106.3 (2013). The United Nations describes the human right to water as “indispensable” and “a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights.”8United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. “General Comment 15.” November 2002 at 1. Yet today, more than one million people across California do not have access to safe drinking water.9Del Real, Jose A. “They grow the nation’s food, but they can’t drink the water.” New York Times. May 21, 2019; Smith, Haley. “Dirty water, drying wells: Central California shoulders the drought’s inequities.” Los Angeles Times. September 2, 2022. Inequitable water quality and access is a burden predominantly shouldered by low-income communities and communities of color — often a result of racist zoning policies that isolated Black, Latinx, and Indigenous folks from municipal services and water systems.10Chiriguayo, Danielle. “Drought worsens Black rural communities struggle to find water.” KCRW (CA). May 5, 2022; Méndez-Barrientos, Linda E. “Race, citizenship, and belonging in the pursuit of water and climate justice in California.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. November 2022; Bliss, Laura. “Before California’s drought, a century of disparity.” Bloomberg City Lab. October 1, 2015. This historic and ongoing exclusion is compounded by water allocations that continue to favor large agribusinesses over people, and a sustained lack of urgency from the state to address inequities in water access.11Food & Water Watch (FWW). “Big Ag, Big Oil and California’s Big Water Problem.” October 2021; Smith (2022); Cagle, Susie. “’Lost communities’: Thousands of wells in rural California may run dry.” Guardian. February 28, 2020; London, Jonathan et al. UC Davis Center for Regional Change. “The Struggle for Water Justice in California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Focus on Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities.” February 2018 at 8 to 11.

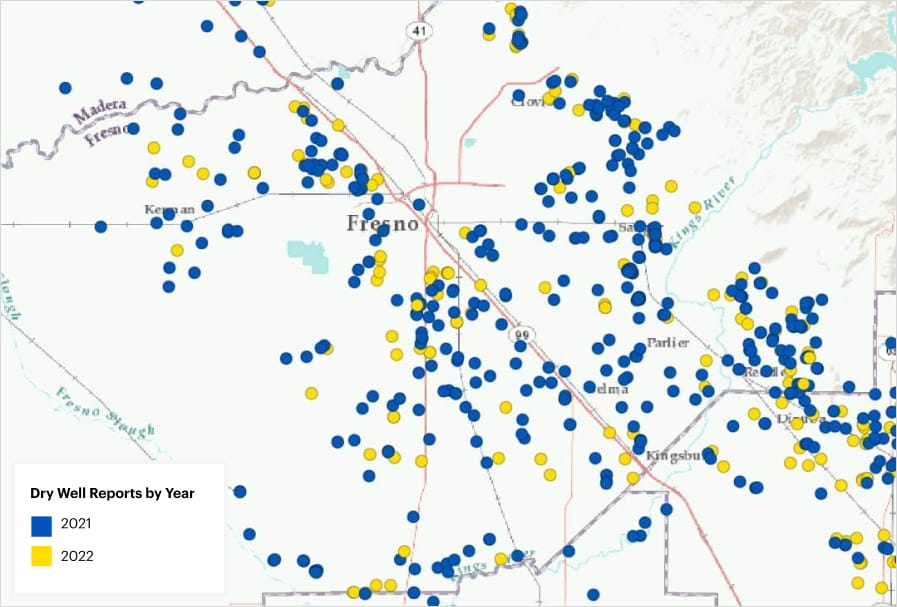

Each dot on the map below represents a report of a dry well filed with the California Department of Water Resources from January 2021 to November 14, 2022. There have been nearly 2,400 reports made in the last 22 months. And since this data is all self-reported, this is almost certainly an undercount of the true number of dry wells in California.

Source Data: California Department of Water Resources (DWR).

In a blistering audit of the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) released in July 2022, state auditors estimated that one million people across California do not have access to safe drinking water because they receive water from a system that fails to meet basic quality standards. There are approximately 370 water systems across California — serving more than 920,000 people — that are failing to provide people with clean and safe water. These failing systems are concentrated in the Central Valley and serve predominantly low-income residents. The audit identifies even more systems that are at risk of failing to provide safe water and emphasizes that as California continues to experience a prolonged drought, water quality will continue to suffer. Water systems on this list only include those with at least 15 service connections — not smaller systems or domestic wells, some of the most vulnerable of California’s water infrastructure.12Auditor of the State of California. “State Water Resources Control Board: It lacks the Urgency Necessary to Ensure That Failing Water Systems Receive Needed Assistance in a Timely Manner.” July 2022 at 1, 7, 8, and 18; Cagle (2020); Pace, Clare et al. “Inequities in drinking water among domestic well communities and community water systems in California, 2011-2019.” American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 112, No. 1. January 2022 at 96.

…state auditors estimated that one million people across California do not have access to safe drinking water because they receive water from a system that fails to meet basic quality standards.

Tombstone Territory is one of these communities suffering from lack of water access. Community members here have been demanding for years that California address water inequities and water abuses by powerful corporations. We spoke with four residents of Tombstone this fall about their experiences having their wells run dry and what they hope for the future of their community.

Carolina’s Story

Carolina Ledesma — a mother of five and longtime resident of Tombstone Territory — described the moment she first noticed something was wrong with her well back in 2018. Pregnant at the time with her youngest, who is now 4 years old, Carolina panicked when air and sand spluttered out of the faucet she was using to bathe her children. She had no idea what to do or what was happening, but the answer was soon apparent. Her well had run dry, and now the family did not have water source for drinking, cooking, washing dishes, doing laundry, bathing, or flushing toilets.

Carolina recalls the pain of sending her children to school without baths, and the strained conversations with them about why their water was suddenly gone. She stopped wanting to go out, worried about the way she smelled. Cleaning the house was out of the question without water. While her husband told her everything would be okay, Carolina couldn’t help but feel confused and sad, and desperate to find a solution.

At first, neighbors would give the Ledesmas water from their wells. Eventually, Carolina connected with an organization that provided bottled water and fixed their well. But this was only a temporary solution.

“We already knew that it’s going to run out,” Carolina said. And before long, it did. This time, her neighbors stopped sharing water because, as Carolina explained to us, they were afraid their own wells could run dry, that this could happen to them next. Currently, Carolina and her family have a tank for water they get refilled as they wait to be connected with municipal water from the city of Sanger or to get help in drilling a new well.

“I want them to touch their hearts, for them to give us the value that we all deserve as humans.”14Note: Our interview with Carolina was done in Spanish, with interpretation from Mariana Alvarenga. The audio recording of Carolina’s interview was transcribed into English by TransPerfect.

Losing your water alters every aspect of your daily life. Carolina tells us that having folks from LCJA like Mariana listen to her story and bring attention to this issue is very important to her. This is one of many interviews she has done to get people around the state to pay attention to small communities like Tombstone Territory and, most importantly, get people in power to do something to protect their water. “I want them to touch their hearts, for them to give us the value that we all deserve as humans,” Carolina urges. “I would like for them to listen to us, because…we have our children, and we need the water.”

Looking around her community, Carolina describes seeing ranchers use lots of water. She wants them to cut down on their water waste and use water more efficiently with better equipment and technology. And as Carolina knows all too well, as large farms and ranches use more and more water, people with shallower wells who lack the money to drill deeper will suffer. “I wouldn’t want anyone else to go through what we went through — they are days of desperation,” she tells us.

Michael and Anita’s Story

Michael and Anita Torres live in Tombstone Territory with their two children, their grandchild, and Anita’s brother. Tombstone was supposed to be a dream come true for the newly married couple when they moved in 24 years ago. Their property has an enormous backyard with a fruit garden and a tree whose branches provide shade on hot days. But about a year ago, while Michael was watering his lawn, he noticed that the water was sputtering. He called a driller, who lowered the well pump by eight feet, assuring Michael that the deeper well should last him another 10 years. Less than a year later, the well ran dry again. “I didn’t want to believe it,” Michael thought. He remembers seeing his neighbors’ wells dry up, but never realized it could happen to his family. “A year ago, I told myself, ‘it’s not going to affect us in any way.’ But it was a shock when it did.”

Right now, a truck refills Michael and Anita’s water tank once a week, enough to live on but not enough to go back to the way things were before their well went dry. Anita has to say no to the kids when they want to play in the shower, and there’s not always enough water to wash their clothes or their bodies. Every aspect of their daily lives is impacted. But other than the tank, their options for water are limited. Drilling a new well is prohibitively expensive. One of their neighbors drilled a new well that cost $35,000. Another neighbor was quoted $55,000. But as folks in Tombstone know all too well, there is no guarantee that a new well will last.

Yet even while Michael and Anita carefully budget their water use and watch their neighbors’ wells run dry, they see new almond acres being planted all around them. “It’s not fair,” Michael told us. “They’re telling us to cut back. But here, they’re allowing these farmers to do almonds.” Almond acreage is expanding all over the Central Valley, and farmers are drilling deeper and deeper to reach groundwater. To Michael, this just doesn’t make sense.

Both Michael and Anita think a lot about their kids and grandchild and how water shortages will impact them. With that in mind, Anita makes trips to Sacramento to tell policy makers about the severity of the drought and water crisis hitting communities like their own. “It hurts us to go through this,” she says. “It’s not fair. It’s hard.” She also spends time recruiting neighbors and friends to come out to community meetings and talk about the water situation, connecting them with organizations like Leadership Counsel. Anita knows that this is necessary work to protect the water for her kids. And for all the hardship they experience, the Torres family knows there are others in the Valley who have even less water.

Michael tells us he knows people on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley are dealing with dry wells and contaminated water too, and not everyone has been able to access water tanks. “We are some of the lucky ones.”

Domingo’s Story

Domingo Gonzalez thinks a lot about future the generations who will live in Tombstone. He knows that this area can flourish when folks have their water needs met. The eighty-six-year-old has lived in Tombstone Territory since the 1980s. He has several children and two grandchildren, so explaining to his grandkids that they can’t play in the shower and they have to be very careful with their water use is painful for him.

Since moving to Tombstone, Domingo has experienced water shortages and issues with his well, but nothing as critical as this year. After his well ran dry, he reached out to a well drilling company and was quoted a $35,000 fee for drilling a new, deeper well. “In this neighborhood, nobody has $35,000 to spend,” he said.

It’s no secret in Tombstone that large farms have senior water rights, more water allocations, and the money to drill the best wells. “The farmers always get the best water. And this year it’s more devastating because we see water flowing everywhere except for over here,” Domingo explains. And while residents in places like Tombstone should be able to access groundwater, they’re increasingly being cut off as the water tables lower due to the massive water use of industrial agriculture.

“Here in this community, we need water,” Domingo says, addressing Governor Newsom directly. “The only thing that stops us from drilling is because there’s no money. We have kids that are growing and not having any water. They need to have their bath every night. And pure drinking water. And we don’t have that. Governor Newsom, we need water. We need it for our children and for our families.”

“We have kids that are growing and not having any water.”

One water tank is not a solution to this problem. Domingo wants to see the Governor take bigger steps towards fixing water allocation to benefit people and not big farms. He wants people in his community and folks who hear his story to talk to their elected leaders; they should know what is going on in places like Tombstone Territory.

Conclusion

The drought is far from over, and the situation in rural communities across the Central Valley is only predicted to get worse. Self-Help Enterprises, a local community development organization that provides many dry well owners with bottled water and water tanks, estimates that around 8,000 wells could run dry in the next few years, based on SWRCB aquifer risk-mapping data.15Partlow, Joshua. “As California’s wells dry up, residents rely on bottled water to survive.” Washington Post. November 14, 2022. There is a project currently underway to connect all homes in Tombstone Territory to municipal water services from the nearby city of Sanger, providing a reliable source of water to the community.16California Natural Resources Agency. “Project: City of Sanger – Tombstone Territory Water Connection Project.” Available at http://bondaccountability.resources.ca.gov/(S(zdajug55psahdk45v25tftja))/Project.aspx?ProjectPK=37405&PropositionPK=49. Accessed October 2022. Yet as residents of Tombstone told us, this may come with its own challenges and will not address the nearby farms planting more and more thirsty almonds every year. Protecting water affordability will be critical in any proposed solutions.17Pineda, Dorany. “As drought drives prices higher, millions of Californians struggle to pay for water.” Los Angeles Times. October 24, 2022. Drilling new wells, testing new wells for contaminants, trucking in water, buying bottled water, and receiving water from municipal consolidation projects all cost money and can raise the cost of water for residents.18Cagle (2020); London (2018) at 8; California State Water Resources Control Board. Groundwater Ambient Monitoring and Assessment Program. “A Guide for Domestic Well Owners.” March 2015 at 10.

A local community development organization estimates that around 8,000 wells could run dry in the next few years, based on SWRCB aquifer risk-mapping data.

At the state level, Governor Newsom has focused his recommendations to address the drought on voluntary cutbacks in urban areas, while rural communities suffer water shortages.19Ramirez, Rachel. “As California’s big cities fail to rein in their water use, rural communities are already tapped out.” CNN. June 6, 2022. His latest plan to adapt to California’s drier, hotter future emphasizes funding industry schemes like ocean desalination, wastewater reuse, and constructing tunnels to divert water around the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta.20California Natural Resources Agency et al. “California’s Water Supply Strategy: Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Future.” August 2022 at 5 to 6 and 16. All the while, Newsom has done nothing to rein in the enormous water use by massive almond farms and mega-dairies that operate throughout the Central Valley.

As Newsom and the SWRCB are failing to take on the biggest water abusers, the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability (LCJA) is doing vital work supporting residents and communities in advocating for funding for water infrastructure, while also fighting the root causes of water inequity. Mariana Alvarenga, a policy advocate with the LCJA, connected us with Carolina, Michael, Anita, and Domingo after having worked in Tombstone Territory for many years.

If Governor Newsom truly wants to be a climate leader, he must address California’s long-term water inequities and prioritize people over agribusiness and fossil fuel corporations. The first steps are cutting off permits for fossil fuel operations and new and expanding mega-dairies, while declaring almonds and other nut crops a non-beneficial use of California’s water resources. It’s time for Governor Newsom to follow through on the promises he made on Carolina Ledesma’s doorstep in 2018. It’s time for California to treat water as a human right — not a commodity to be allocated to the highest bidder.

Water is a human right. Ask Governor Newsom to do the right thing.

Endnotes