Help Us Pass Federal Farm Legislation!

What You’ll Learn From This Report

- 1: A Broken Food System

- Deciding what and how to farm should be left to farmers, not corporations

- 2: From Extractive To Regenerative Food Systems

- The farmers at the forefront of this movement

- 3: Rebuilding Regional Food Hubs

- Rebuilding regional food hubs connects farmers and eaters, and reduces the monopoly corporate agribusiness has on the food system.

- 4: Policy Recommendations: A Roadmap To A Just Transition

- Here are our policy recommendations on how to pivot to this much-needed systemic change.

- 5: Conclusion

- We can build regenerative food systems

Part 1:

Our Food System Is Broken

Deciding what and how to farm should be left to farmers, not corporations.

Corporate monopolies control food production.

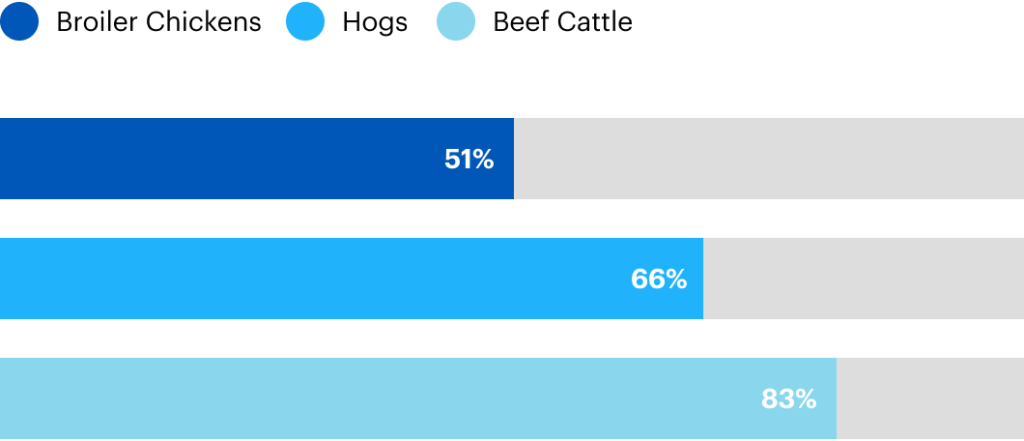

Today’s supermarkets seem like the pinnacle of choice and variety. But consumers might be surprised to learn that this choice is really a façade, and that a few companies dominate the market in each food category. Your steak? Just four companies slaughter 83 percent of all U.S. cattle (see Figure 1).1 Your flour? It likely comes from Ardent Mills or ADM Milling, which together mill half of all U.S. wheat.2 And then there are companies that profit from value-added processing of raw ingredients. The jars of Gerber, boxes of Cheerios and Lean Cuisine, and tins of Fancy Feast in your shopping cart are all Nestlé-owned brands.3 Agribusinesses make consumers feel like they have ample choices, while forcing them to buy much of their food from just a handful of corporations.

Livestock Farmers Sell into Highly Concentrated Markets

Market share of top four processing firms

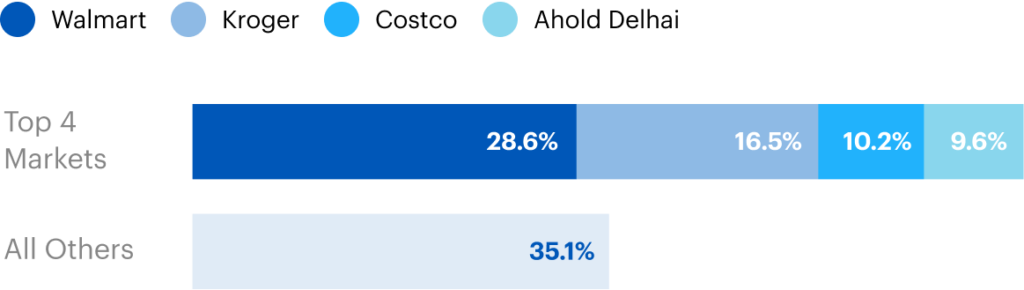

Even supermarkets themselves have gobbled up competitors and secured huge market shares. Four companies — Walmart, Kroger, Costco and Ahold Delhaizea — control 65 percent of the grocery market.5 This stranglehold raises food prices and wipes out local grocery stores, reducing food access in both rural and urban communities (see Figure 2).6

Supersizing the Supermarket: National Market Share

Less competition among agribusinesses means higher prices and fewer choices for consumers. But for farmers and the rural communities they support, it is a fight to survive.

Corporate agribusinesses gut rural America.

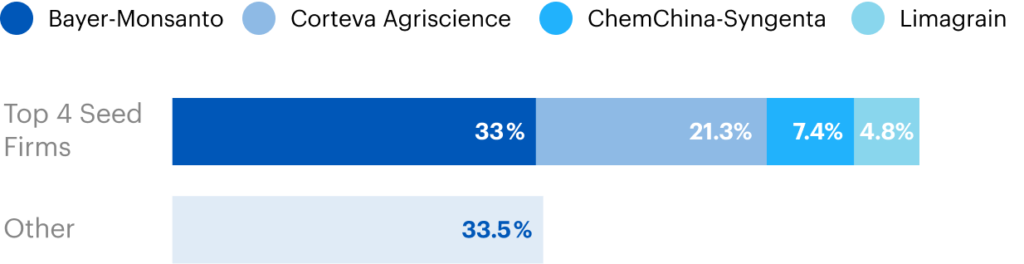

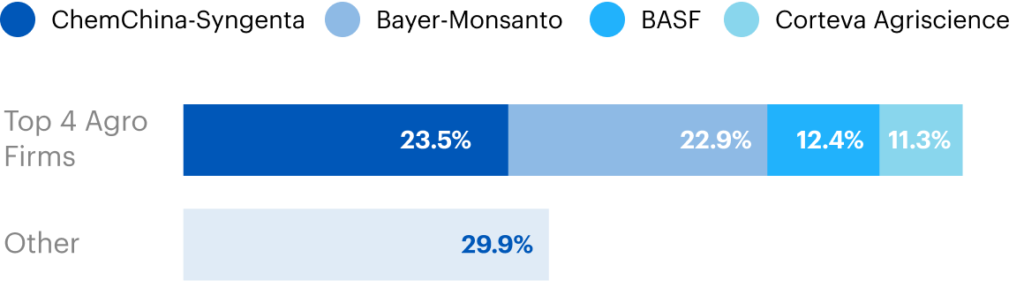

Market consolidation has wiped out competition, giving farmers fewer choices when they buy seed and feed and when they bring products to market (see Figure 3 on page 3). As a result, they face both rising costs and stagnating income.8 In fact, today’s median farm income is negative $1,840; many farms manage to stay afloat through off-farm income.9

Ironically, while farmers have little power in our industrial food system, they often receive much of the blame for that broken system. Misguided policymakers and others deride farmers for overproduction, for receiving subsidies, or for participating in contract farming when all of these are symptoms of the underlying dysfunction in the food system.

Market Share Of Top Four Seed Firms

Market Share Of Top Four Agrochemical Firms

Corporate consolidation also hurts rural communities. Local slaughterhouses and flour mills have shuttered as processing facilities became fewer and larger. Revenue that once circulated in rural communities and built thriving main streets is now funneled to Wall Street and far-away corporate headquarters.11

Corporate agriculture perpetuates exploitation and racism.

Our farming system rests on stolen land, stolen labor and stolen resources, including forced removal of Indigenous peoples, the enslavement of African Americans and the sharecropping model. These systems persist today in vertically-integrated livestock systems that lock farmers into abusive contracts and high debt, the patenting of Indigenous seed varieties, the freezing-out of farmers of color from federal loans and subsidies, and the exploitation of low-wage labor in dangerous conditions in our nation’s produce fields and slaughterhouses.12

Industrial agriculture is extractive.

The industrial farming system focuses on squeezing out as much profit as possible, with little regard for long-term environmental ecological or public health impacts. Planting monocultures year-after-year can impair soil health.13 So does spraying synthetic pesticides. Intensive practices also harm bees and other pollinators and microorganisms that make up healthy ecosystems.14

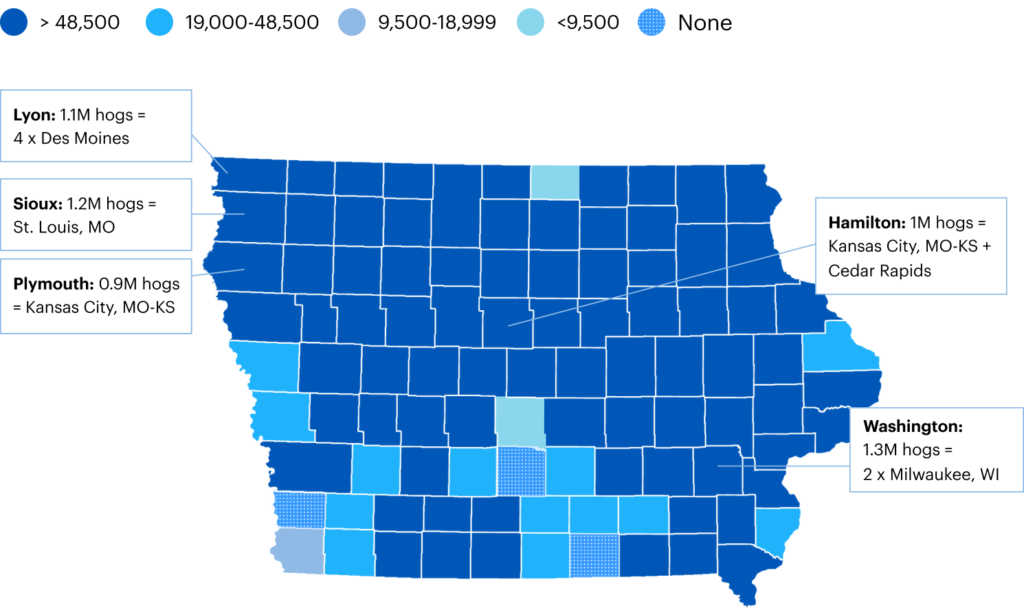

Factory Hog Farm Counties Produce as Much Waste as Metropolitan Areas

Industrial agriculture pollutes the environment and fuels climate change.

Factory farms confine thousands of animals in inhumane, unsanitary conditions. They produce more manure waste than can be sustainably disposed and increase the risk of diseases jumping from livestock to humans (See Figure 4).16 In many parts of the country, factory farms are concentrated around communities of color and low- income communities, making them environmental justice catastrophes.17

Rural communities bear the brunt of pollution from industrial farming, from pesticide exposure to toxic emissions from factory farms.18 Yet these impacts reach far beyond the farm; nutrient runoff from manure and pesticide application pollutes waterways, contributing to fish kills and aquatic “dead zones” from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.19 Pesticide residue is found on all food types of food, from organic produce that was never sprayed with pesticides to human breast milk.20

Agriculture is also one of the largest human sources of climate change; across the entire production chain, it contributes 19 to 29 percent of all human-sourced emissions. Overproduction of commodities and meat, food waste, growing crops for fuel, and use of synthetic fertilizers produced from fossil fuels all enlarge this footprint.21

Our food production chain is not resilient.

Decades of unchecked corporate consolidation has worn away our food system’s resilience.22 For instance, large, centralized processing facilities replaced the regional slaughterhouses and dairy processors that once dotted the rural landscape, leaving farmers with fewer options for marketing their products.23 When some of these large facilities closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, many farmers were left with no choice but to euthanize livestock or dump milk — gut-wrenching scenarios that would not have been as widespread if we still had networks of smaller facilities serving local markets.24

Our food system does a poor job of feeding people.

Even after accounting for commodities grown to feed livestock and produce energy, the U.S. still has roughly 4,000 calories of nutrients available per day per capita.25 Yet nearly one in seven children live in food-insecure households.26

Much of what goes into deciding what and how to farm is shaped by agribusiness, not farmers. Corporations set farm markets and policy.27 We need to join farmers and food chain workers to break Big Ag’s stranglehold and rebuild our food systems so they work for everyone. It can be difficult to imagine what alternatives to the industrial system might look like. We can start by learning from those at forefront of this movement, who are building healthy farmland and rural communities through regenerative agriculture.

Part 2:

From Extractive to Regenerative Food Systems

The farmers at the forefront of this movement

Regenerative agriculture is generating a lot of buzz today, with everyone from food activists to big agribusinesses floating the term. But with no unifying definition, the term “regenerative” can take on different meanings.28 So let’s start by defining what we mean by “regenerative food systems.”

Regenerative food systems are those that invest in the long-term health and fertility of farmland; build soil and prioritize soil health; and rely on natural rather than synthetic inputs. They embody these principles along each step of the food supply chain — investing in local economies; providing farmers and food chain workers with living wages and safe working conditions; and addressing racial and economic injustice. The regenerative movement shares roots with organic farming, a reaction against the environmental degradation caused by industrial farming. Today, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversees the National Organic Program, creating standards for the organic label and certifying compliance. Regenerative farming, on the other hand, has no federal standards or label any farmer or food company can market their products as regenerative.

Can we feed the world through organic agriculture?

The giant agribusinesses that profit off of the current industrial system claim that it is the only way to feed a global population that is estimated to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050.109 This is simply not true; a growing body of research affirms that regenerative practices can increase long-term yields and potentially close yield gaps with conventional systems.110 In fact, the United Nations urges a rapid shift to regenerative practices to increase productivity, reduce hunger and avoid catastrophic climate change.111

Simply put, giant agribusinesses exploit hungry people for profit. If they were truly motivated to end hunger, they would not support a farming system that prioritizes growing crops for fuel, fiber and animal feed. Likewise, they would not prevent farmers from saving seed nor would they appropriate and patent native seed varieties.112 And they would not support global trade policies that drive traditional farmers off their land and create new generations of impoverished, hungry people.113

Poverty and inequality drive hunger, not scarcity. We grow more than enough calories to feed the world, yet roughly 815 million people worldwide go hungry, 75 percent of them family farmers who together produce the majority of the world’s food.114 According to the United Nations, regenerative agricultural practices can help close this hunger gap. Centering family farmers and breaking the stranglehold that corporate agribusinesses have on farmers are key to this transformation.115

Some regenerative advocates market it as a new concept that goes beyond the limits of organic agriculture.29 This is a disservice to the organic community and its decades of work in strengthening the integrity of the organic label and increasing federal funding for organic research and adoption. It also erases centuries of contributions from indigenous and other farmers of color who farmed regeneratively long before the term emerged.30

In this piece, we use the term “regenerative” as an umbrella term for sustainable farming systems. Some of the farms featured are certified organic whereas others have not sought certification. What unites them is a holistic method of farming that seeks to regenerate, rather than extract, natural resources.

Putting animals back on the farm: Keenbell Farm

One vital shift in repairing our food system is to move live-stock off of factory farms and back onto pasture. Managed grazing distributes manure in sustainable amounts, building soil and recycling nutrients. And integrating livestock into crop rotations can control weeds, increase yields and reduce fertilizer use. Extensive research concludes that “livestock provide the missing element needed to develop sustainable systems, particularly in terms of soil health.”32

Keenbell Farm near Rockville, Virginia embraces this approach. Co-owner CJ raises cows, pigs and chickens on pasture as well as specialty grains. CJ sustainably manages the cows’ grazing to allow pasture to regrow and prevent manure accumulation. The chickens follow the cows to manage flies, sleeping in mobile chicken coops and spending their days foraging for insects. Keenbell’s hogs are also on pasture 100 percent of the time, rooting for much of their food.

Both chickens and hogs supplement their forage with a blend of grain byproducts from the farm’s fields — one more way to “keep the closed loop,” according to CJ. They manage these grain fields regeneratively, planting just one harvestable crop each year, as opposed to the two-year rotation of corn, wheat and soybeans typical in Virginia. This allows Keenbell to avoid tilling the soil and virtually eliminates the need for chemical herbicides.

Keenbell harkens back to an earlier era, before chemical inputs compensated for a lack of agricultural diversity and poor soil management.33 In fact, CJ finds a wealth of knowledge from farming books published before the 1950s. “A lot of what is going on today with regenerative agriculture is the way my grandfather farmed, minus the tillage,” he says. However, farms like Keenbell have had to relearn many of these practices, often reembracing diversification after experiencing firsthand the ecological and economic damages from industrial, specialized farming systems.

Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

CJ’s grandparents purchased the farm in the 1950s, raising cattle and producing eggs for the local market. In the 1970s, they expanded to include hogs, but the hog market crash of the 1980s convinced them to keep the focus on cattle and cropland. CJ took over in the early 2000s and began an effort to restore land that was previously rented to a conventional grain farmer. They converted hundreds of acres to pasture and to specialty, non-GMO grains sold to local bakers and distillers.

“I don’t tell you I’m a cattle farmer or chicken farmer,” says CJ. “I’m a soil farmer: My goal is to use the animals, the crops, the forage as tools to manage the soil.” For instance, CJ restored a degraded piece of land by using regenerative practices to double the soil’s organic matter and increase its water-holding capacity. “You couldn’t put a dollar figure on that,” says CJ. “You have to look beyond the checkbook register to really calculate the true benefits of conservation.” Numerous studies confirm what CJ has experienced firsthand: Regenerative practices can repair degraded soil, reduce costs and close yield gaps between conventional systems.34

Keenbell Farm is a glimpse into regenerative farming systems in the 21st century. But it can be risky for farmers to embrace new production systems, especially when public funding is geared to propping up industrial agriculture’s status quo. CJ believes that if more farmers were able to participate in cost-sharing programs that incentivize sustainable practices, they would understand the economic benefits for their operations.

Lack of access to open, competitive markets is another barrier to shifting to more diversified farms. Open cattle markets and regional flour mills have been largely wiped out by corporate consolidation, leaving farmers with few potential buyers.35 Keenbell solves this problem by selling meat directly to consumers and grains to local bakeries and distilleries. CJ recognizes they are fortunate enough to be located near Richmond, Virginia, with ample middle- and upper-income customers eager for locally-produced food. This direct-to-consumer model is less feasible for farms located in more remote or impoverished areas.

One-third of U.S. farmers are 65 or older.36 Whether or not the next generation will want to take over family farms remains to be seen, especially considering that the average farm income is in the negative.37 “We are facing the potentially largest transition of land in history,” says CJ. “We’re at the pinnacle of opportunity to empower farmers and increase the number of farmers by having a more regionalized food economy, or further go down the path of a global, centralized food system.”

Taking advantage of that opportunity requires public investment in regenerative, diversified practices. We also need to boost funding for the infrastructure needed to connect farmers to local eaters and raise farm income. As CJ puts it, “Sustainability is also about economic stability: Making sure you’re commanding enough prices to cover your cost of goods with enough profit to maintain your operation and gain a living wage.”

The secret to successful farming: Master Blend Family Farms

When you think of a North Carolina hog farm, you might picture rows of confinement barns and manure lagoons. Factory farms displaced many of North Carolina’s smaller, family-scale hog farms, with a third fewer today compared to twenty years ago.39 However, independent hog producers are meeting the growing hunger for local, pasture-raised pork — and building robust communities in the process.

Ron Simmons grew up in urban areas, and visiting his great-grandmothers’ hog farm persuaded him against a farming career. “Whenever I saw her pigs, I promised myself I would never do it.” He worked a regular day job for a couple of decades. Eventually, he gravitated towards the country, where he found a unique business opportunity: Meeting the growing demand for healthy, pasture-based meat. He switched careers and dove headfirst into hog farming, opening up Master Blend Family Farms38 outside of Kenansville, North Carolina in 2012. “I’m sure that my grandparents are laughing now,” he jokes.

As a beginning farmer, Ron sought out seasoned hog farmers. He wanted to know whether there was a secret handbook or blueprint on how to be successful. “Naw, dude, you have to wing it!” they laughed. So he asked every question he could and took advantage of the nearby cooperative extension office and community college classes. And he learned about humane and sustainable practices through the Animal Welfare Approved label, where farmers commit to standards such as avoiding animal byproducts in feed and implementing pasture rotation.40

Ron quickly learned that there is more to farming than simply playing in the dirt. “Farmers wear so many varieties of hats,” he says, from livestock breeders and caretakers to accountants. They also need to be willing to take risks and seek out opportunities to diversify their income. Essentially, independent farmers like Ron are like other entrepreneurs, just with a bit more dirt under their nails.

Ron has a natural head for business, contributing to his farm’s success. He forges relationships with restaurants, caters events and even sells to churches to create more exposure to the Master Blend brand. He also runs an on-farm store where he sells small cuts to customers. This diverse customer base proved an invaluable asset at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when demand from local restaurants bottomed out. The farm store was “the saving grace,” allowing him to sell meat originally destined for restaurants. In fact, spurred on by supermarket shortages of meat, he got calls from customers in cities as far away as Raleigh and Chapel Hill looking to buy pork in bulk.

Independent hog farms are not tied down by contracts with meatpacking giants, which dictate all aspects of production and set prices. As small businesses, they tend to make more purchases locally and recirculate revenue into their communities.41 A wealth of data shows that small- and mid-sized family farms are vital to the economic and social health of rural communities.42 But independent growers need processors to work with and markets in which to sell. Both are barriers preventing many farmers from operating more humane operations like Master Blend.43

As the meat packing industry consolidated, slaughterhouses and processing plants became fewer but larger, and increasingly relied on exclusive contracts with large-scale operations. Consolidation also drove down the prices farmers received for their hogs. Many farmers were faced with the choice between expanding their operations through contract production or abandoning hog farming altogether.44

“The very first time I entered a processing plant and said I want them to process for me,” says Ron, “they bust out laughing. ‘It’s amusing and cute but you aren’t big enough.’” He didn’t back down, but invested in breeding sows and production boars to grow his operation, giving careful consideration to genetics to produce a healthy and desirable product. Today, he raises around 150 market hogs — significantly smaller than the 8,000 or more on the average North Carolina factory farm45 — but large enough to find a processor. Going independent is challenging but “one of the pros is you get to name your price, and still be able to offer a wholesome, premium quality product.”

We need to shift to smaller, family-scale livestock farms like Master Blend Family Farms to rebuild rural communities and stop the environmental destruction caused by factory farms. And farmers need training from those who have already gone down this path. Ron’s success sparked speaking opportunities across the state. Reluctant at first, he soon recognized that being a spokesperson for pasture-based farms is just as important as his roles on the farm. “I read all the time that farmers are a dying breed, so if I have the opportunity to speak at a university or a local school, I always try to push the idea of finding more farmers and diversifying the pool.”

Connecting to our roots: Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute

Whenever an alternative to the polluting, industrial agri- cultural system gains traction, Big Ag schemes to profit from the hype. Today, agribusinesses are appropriating the term “regenerative” into their existing industrial models.

General Mills pledged to advance regenerative agriculture on a million acres of farmland, while chemical giant Syngenta claims that their pesticides complement regenerative practices.47 But regenerative farming is nothing new; societies across the millennia fined-tuned agricultural practices and seeds in response to their environments — all without the quick fixes peddled by Big Ag.

Native American communities of the Southwest cultivated numerous varieties of seeds and agricultural practices rooted in the desert climate, where thirsty crops like corn thrived.48 These interconnected agricultural systems were the fabric of Indigenous southwestern cultures and communities. But Spanish colonial domination, followed by violent U.S. policies of relocation and assimilation, tore communities away from their cultural roots. Government rations replaced traditional diets for many Indigenous peoples. Reconnecting with traditional Native food systems can improve health49 while continuing cultural practices and environmental sustainability.

Roxanne Swentzell, an artist from Santa Clara Pueblo in northern New Mexico, founded the Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute in 1989 with these goals in mind. Flowering Tree’s first project transformed the barren driveway into a forest of fruit trees, not a small under-taking in the desert with its cold winters and short, hot growing seasons. They started with nitrogen-fixing shrubs and trees, and the belief that a plant “will grow if you take care of it,” says Roxanne. “And after 30 years things get pretty big.” Today, the 1/8-acre permaculture site boasts fruit trees, vegetable crops, and even goats and chickens. It is a testament to how careful attention to the local ecosystem’s needs can help agriculture flourish even in the most challenging environments.

“It’s really important that people identify with place,” says Roxanne, explaining how Flowering Tree works to continue Pueblo culture by encouraging the Tewa language, teaching pottery and growing traditional foods. Pueblo people were not displaced from their original homelands like many other Native American tribes, but still lost ties to their food culture. “When we lost our farmers, we lost our health,” says Roxane, addressing the rise in diet-related diseases as community members purchased more and more food in town. She and other participants of Pueblo descent undertook an experiment where they ate nothing but pre-contact foods of their ancestors for three months. Participants showed significant weight loss and lower levels of cholesterol and blood sugar after the study. Moreover, “because the diet was based on a cultural identity — this is the food our people used to eat — there was also a reconnecting that none of us realized would happen.”50

Roxanne works to cultivate connection to the Pueblo land and traditions in the next generation. She shares seeds with schoolchildren, emphasizing that they are the plants’ “caretakers” in order to encourage a sense of responsibility for carrying on the tradition. She also plants traditional Pueblo crops at risk of extinction and saves seeds in her seed bank. “Traditionally, those crops belong to us, or we belong to them; we see them as sisters and brothers, and we’ve grown and evolved together.”

Indigenous Americans’ contributions to global agriculture are substantial: Many crops eaten worldwide originated in the Americas, including staples like corn and potatoes.51 There were nearly 300 varieties of corn alone by the onset of European colonization, cultivated for both subsistence and ceremony.52 Today, however, over

99 percent of U.S. corn acreage is “field corn” destined for cattle feed, processed food or ethanol, with only a sliver of sweet corn grown for direct human consumption.53 Most field corn is genetically modified to be resistant to herbicides like Roundup and is grown on soil-depleting monocultures, making these systems vulnerable to plant pests and diseases.54

Juxtaposed to this are Indigenous communities like the Santa Clara Pueblo, where agricultural practices are rooted in the local ecosystem and seeds are chosen for their nutritional benefits and local adaptiveness. But we must also take care not to appropriate Indigenous knowledge. Colonialism’s long shadow extends into today’s food system, including with “biopiracy,” when agribusinesses patent Indigenous seeds or practices without permission or compensation.55 Treating regenerative agriculture as a “new,” profit-generating scheme risks further exploitation of Indigenous seeds and practices.

“Let’s take it back from corporate America,” says Roxanne. She adds, “I do think women are leading this big movement. We’re coming together to say we’ve had enough.” In the summer of 2020, she and other women from her tribe grew ceremonial corn on a communal field, providing a rare opportunity during the COVID-19 pandemic to socialize at safe distances. “It’s a beautiful event, and when you hand that to a big corporate whatever to produce our food, we don’t have these amazing gathering moments.”

Restoring prairie with regenerative grazing: The Rider Ranch

Jed Rider didn’t grow up raising cattle, but on an irrigated sugar beet farm near Trenton, North Dakota. In high school, he went to work for a nearby rancher, and later married Melissa, whose family raised cattle and grains outside of nearby Alexander. This introduced him to conventional ranching in the Great Plains, where most cattle begin life on pasture-based cow/calf operations before being “finished” on grains in feedlots.

Managing Melissa’s father’s herd and helping his uncle farm sugar beets proved to be an impossible balancing act, and it began to take a toll on Jed’s health. At the time, his sister Kalie was finishing her Master’s thesis on the health benefits of grass-finished beef. Their conversations around the health implications of different ranching systems led to a deeper one about holistic cattle operations. “That year, I quit raising sugar beets and started eating better and ranching better, and it just kinda exploded from there,” says Jed.

Soil health is at the heart of the Rider’s ranch.56 They move the 200+ cow/calf herd every one to three days during the growing season, leaving some vegetation behind and allowing it to regrow before it is grazed again. They bale fields not yet ready for grazing, providing winter feed; but unlike most ranches, they leave the bales in the fields and bring the cows to them. This allows the Rider’s cows to be on pasture even throughout North Dakota’s long winter months, where they are protected from the weather through coulees and shelter belts.

In turn, these practices have provided many benefits to the Rider’s land. “When somebody asks me how much rain I got, I say ‘all of it’,” Jed jokes, referring to improved water retention thanks to regenerative management.

Managed grazing can restore degraded rangeland, improve soil health and avoid excessive manure accumulation associated with factory farms. Additionally, grass-finished beef systems have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and in some instances are carbon-sinks.57

The Rider’s ranch, for instance, is virtually input-free. Cattle feed on pastures of perennial grass, much like the bison that once roamed the Great Plains. This is in sharp contrast to the industrial agriculture system, where large agribusinesses profit from technological and chemical “fixes” for problems stemming from poor land management. For instance, planting feed corn for factory farms on continuous monocultures makes these systems vulnerable to weeds.58 Agribusinesses peddle chemical herbicides, putting farmers on a never-ending treadmill that requires greater application rates and newer formulations when herbicide resistance predictably develops.59 As Jed succinctly puts it: “We as a society have an economy of making profit centers out of Band-Aids and treating symptoms of things.”

Jed knows firsthand the stubborn nature of farmers, many of whom are resistant to deviating from the practices used by their parents and grandparents. Even grass-finished beef was practically a “cuss word” when the Riders started out, an unconventional approach that to some seemed to eschew the state’s grain economy. However, Jed notes that “if agriculture doesn’t change, there’s not gonna be one.” Poor soil management increases the number of acres needed to farm, while also increasing overhead costs, including more chemicals and expensive machinery. “What kid can afford $3 million in equipment to haul off and start farming?”

This is where farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing is invaluable. Jed and his sister Kalie serve as mentors in the North Dakota Grazing Lands Coalition, where they promote the benefits of regenerative grazing. “Farmers don’t want to go listen to someone who’s never made mistakes and is just getting their experience from reading a book.” says Jed. He hopes that the narrative around farming is changing, a crucial shift in order to mentor the next generation of farmers. “What kid is gonna want to go into something when all we do is complain about how awful it is… Let’s start telling some good stories.”

“Dairy based on our belief systems”: Pure Éire Dairy

Organic certification remains an important pathway for farmers to shift to regenerative systems. Today, farmers who seek to sell their products as organic must go through the certification process and commit to standards including avoiding synthetic inputs and GMOs. This allows them to earn the “organic premium” from their products — the extra money consumers are willing to pay for food carrying the USDA organic seal.61

At its heart, organic is not simply “farming without chemicals,” but a holistic approach to agriculture that builds healthy ecosystems and promotes sustainability.62 Farmers like Jill and Richard of Pure Éire Dairy60 were drawn to organic farming because they believe in these principles and in the importance of providing organic, grass-fed milk to their children. Though they both came from larger dairy operations, they started Pure Éire with just seven cows to see if others wanted the same kind of milk.

Jill describes her organic dairy as a “closed loop”: The cows feed on pasture during eastern Washington State’s long growing season and eat grasses and forage grown on their farm during the winter months. In turn, the cows fertilize the pasture, enriching the soil and avoiding the problem of manure waste disposal that confined dairy operations face. In line with organic regulations, Pure Éire Dairy also refrains from administering artificial growth hormones (used to increase milk production) and antibiotics, whose routine use on conventional farms is linked to the rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria.63

Today, Jill and Richard raise a couple of hundred cows and also own their onsite processing facility. They sell Pure Éire’s products across eastern Washington, and a private-label yogurt to the Seattle cooperative PCC Community Markets. Despite this impressive growth, Jill says, “We’ve never strayed from our mission from when we started this with just seven cows.” Jill and Richard continue to raise 100 percent grass-fed dairy cows, going above what is required by organic standards.64 This results in what she describes as a “fabulously creamy, rich milk,” with higher levels of nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids than both conventional and organic milk.65 Demand for grass-fed milk is growing among consumers who want food that aligns with their values of healthy food and sustainable practices.66

The higher premiums consumers pay for organic milk can sometimes offset higher production costs. In 2016, organic dairy farms showed higher returns than conventional ones of similar sizes,67 although Jill notes that the last few years have also been tough for organic dairy as oversupply has driven down prices. But before a farm can achieve organic certification, it must implement organic practices for three years while still selling into conventional markets. This transition period is a “huge challenge for entering the marketplace,” says Jill. Moreover, once a farm achieves organic certification, “you need a contract with an organic handler to ship your milk.” Organic dairies have fewer options for selling their milk, with organic milk products making up less than 6 percent of all fluid milk sold in the U.S.68 Fewer buyers also means less competition that can potentially impact milk prices.

Pure Éire Dairy benefits from having its own processing facility to provide them with more control over their products. They work directly with retailers and consumers to meet their needs, allowing them to operate a successful business. However, most dairy farmers — organic and conventional alike — are “price takers,” with little to no leverage in determining milk prices. And while farmer-owned cooperatives still market the majority of domestic milk, their consolidation in recent years has impacted farmer control and wages.69 As Jill elaborates, cooperatives may increasingly favor contracting with a few large farms rather than several small ones to find efficiencies and economies of scale. Today, the average U.S. dairy cannot even make up the cost of production.70

Farms like Pure Éire Dairy demonstrate the vital role of smaller, family-scale dairies in advancing organic practices and boosting local economies. But thousands of others risk foreclosure in the face of low milk prices and industry consolidation.71 We need to realign our federal farm policy, including creating a meaningful dairy safety net, in order to level the playing field for family farms and rebuild regional food hubs.72

Diversity builds resilience: Graise Farm

Many of us take for granted being able to walk into a supermarket and purchase every variety of food imaginable. We rarely think about where it came from or who produced it. But the COVID-19 pandemic put our food system at the forefront of everyone’s minds, disrupting the supply chain and provoking panic-buying.74

“For some people, farming is a hidden world,” says Tiffany, who runs a small livestock farm with her husband, Andy, south of Minneapolis, Minnesota. When the pandemic hit, they saw a surge in interest from people who wanted to purchase food locally, with some customers commenting, “I never knew this was an option to buy direct from farmers. I never knew all these farmers were out there.”

Tiffany and Andy started GRAISE Farm73 in 2015 as a way to become more self-sufficient and to contribute to the local food economy. Their farm demonstrates that smaller, regionally-based farms and food systems that promote animal welfare and soil restoration can thrive — even in northern regions like Minnesota where the temperature can range from 100° F to -30° F.

GRAISE stands for “Grass-fed Raised humanely Animals In a Sustainable Environment,” a name that is guiding principle for owners Tiffany and Andy. “We raise our animals with respect and allow them to be themselves,” says Tiffany. This includes providing year-round access to the outdoors, where they can express their natural inclinations to root, scratch and peck. Raising their animals on pasture in sustainable numbers aerates the soil and promotes biodiversity. “We’ve moved our pigs across land that hasn’t been touched in 20 years,” says Tiffany, “and it’s helped dig up native seeds, so we’re seeing more diversity in the plants that are growing. We’re seeing more diversity in the birds and the butterflies, insect population, all those things that are important for the farm.”

GRAISE Farm raises hogs and meat chickens for direct sale to customers. They also raise duck eggs that are sold in cooperatives, specialty stores and restaurants across Minnesota and neighboring states. This variety in products and markets helps diversify their income and make their farm more resilient to supply chain disruptions — a literal

example of not putting all of your (duck) eggs in one basket.

Smaller, diversified farms like GRAISE that serve local markets can increase the resiliency of our food systems.75 During the pandemic, GRAISE continued to process their livestock since they rely on smaller slaughterhouses — not the crowded mega-slaughterhouses that became COVID-19 hotspots.76 Other local farms across the country demonstrated their resiliency and flexibility by quickly pivoting from supplying restaurants and caterers to direct sales to consumers, often through social media.77

Even so, many other small farms suffered economic losses during the pandemic, especially those producing highly perishable food like dairy and produce.78 And federal pandemic relief funds largely overlooked smaller farms and those run by beginning farmers and people of color.79 This is part of a wider problem with farm safety net programs that prop up large-scale production of commodities at the expense of small-scale and historically underserved farmers.80

Small, diversified farms can serve local communities and raise animals humanely. But we need to widen our farm safety net to cover more specialty crops and diversified operations, and assist smaller farms and those run by women, people of color and beginning farmers. A wider program of rural revitalization would also tackle issues like broadband and health care access in order to provide the resources for regional food systems to thrive.

Part 3:

Regional Food Hubs

Rebuilding regional food hubs connects farmers and eaters, and reduces the monopoly corporate agribusiness has on the food system.

Farms need access to open, competitive markets to thrive. However, agribusiness consolidation has all but wiped out the nation’s smaller-scale slaughterhouses, grain mills and mom-and-pop grocery stores,81 making it increasingly difficult to imagine a food system that is not dependent on highly consolidated supply chains. The truth is, agri- businesses built the industrial food system over a few decades; we can similarly rebuild this broken system to ensure justice for all farmers, food chain workers and consumers.

Building just, regenerative food systems will not happen overnight. It requires significant public investment and political will. Direct sales and farmers markets are important but insufficient; we must also connect local farms to the grocery stores and restaurants where consumers spend the majority of their food dollars.82 Regional food

hubs can play a vital role, aiding smaller farms with distribution and marketing of their products so they can reach new markets that would otherwise be difficult to enter on their own.83

Common Grain Alliance

How Food Hubs Work

The idea for Common Grain Alliance98 emerged in the winter of 2018, as a group of friends were baking bread together and discussing how difficult it is to find local grain. “If you go to the Shenandoah Valley, you see all this grain infrastructure, silos, row crops,” says founder Heather Coiner.

“The landscape suggests that grains should be growing here, so how come we can’t find any?”

SCROLL SIDEWAYS TO NAVIGATE

Common Grain Alliance

Heather, who owns Little Hat Creek Farm and bakery, started by looking for growers who produced and processed grain in the mid-Atlantic. “We feel strongly that grain is a missing part of the local food table and we want to change that in this area,” she says. In just a couple of years, Common Grain Alliance grew to include over 60 members, connecting wheat growers and millers to local restaurants, brewers and distillers.

Common Grain Alliance’s mission is to revitalize the mid-Atlantic’s grain economy. “We’re trying to tap into the historical infrastructure and skills that got pushed aside by industrial agriculture in the last half of the 20th century,” says Heather. For example, some millers have restored existing stone mills while incorporating modern equipment to take advantage of recent advances in grain milling.

Common Grain Alliance

Common Grain Alliance has received some federal funding to grow its network, including a grant through a USDA program called SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education). But while some Farm Bill programs directly target small-scale growers, Heather says that non-commodity crops are still largely off the radar of most academics and policy experts. “Even with this support, the vibe I get is, this is a fun idea but you are not going to feed millions of people.” Heather hopes that as the Common Grain Alliance grows, so will the political will of its growers and buyers who want grain that is transparently sourced, traceable and grown without chemicals.

Common Grain Alliance

In fact, the pandemic showed the importance of local food chains like those created by Common Grain Alliance. “One thing the pandemic laid bare is the flaws in the global food supply chain. Americans saw empty grocery store shelves — that’s not something most people have seen in their lifetimes. And your local farmers are like, we have grain, we have vegetables… Our supply chain isn’t interrupted because it’s shorter.” Heather is optimistic that for some people, the trends that led people to seek out local food and support nearby farms might endure past the pandemic. “It is worth going out of your way to invest in your local food producers, because when crisis hits, they’re the ones that are still going to have food.”

Small farms often lack the volume and consistency of products to sell directly to a retailer or foodservice institution. Larger institutions prefer to purchase from a single entity rather than several small farms. A food hub can help bridge this divide by connecting several smaller farms with regional buyers. Some food hubs even invest in infrastructure farmers need to bring products to market, like warehouses where food is stored, packed and labeled. What distinguishes food hubs from other local distributors is that they are formed with the goal of improving the economic, social and environmental health of their communities. As such, they are committed to providing farmers with fair prices and longstanding relationships rather than undercutting them in search of the cheapest alternative.84

There are many current efforts to revitalize local food systems through the food hub model. Public investment and incentives can help create similar food hubs across the country that are unique to each region’s geography and food culture.

Paying it forward: Mandela Grocery Cooperative

Before Mandela Grocery Cooperative85 opened a decade ago, the West Oakland, California neighborhood had not had a grocery store for 50 years. Food deserts — or food apartheid, a term preferred by many activists86 — are largely a result of grocery consolidation that wiped out smaller grocers in urban and rural areas alike. Large chains restructured and put more resources into stores in more profitable areas, reducing food access in lower-income communities.87

Grocery cooperatives combat food apartheid while building local economies. Employees can become “worker-owners,” sharing in profits and losses and participating in oversight. Decisions, therefore, are not made by far-away corporate shareholders, but by the communities themselves. Worker-ownership can also create sustainable, good-paying jobs for employees.88 “Our workers are thinking about long-term and intergenerational wealth,” says Adrionna Fike, one of Mandela’s founders, noting that they look beyond next month’s sales to create goals like building retirement plans.

Cooperatives have long been an act of resistance in our food and farming systems, especially within Black

communities. Farmers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries engaged in informal cooperatives to purchase inputs, share machinery and market products. During the Civil Rights Movement, Black-owned credit unions extended credit to farmers. These efforts addressed the numerous institutional and economic barriers that prevented Black farmers from owning and maintaining farmland, a fight that continues to this day.89

Notably, the local food movement has largely failed to include people of diverse racial and economic backgrounds. Farmers markets and other local food venues remain predominantly white, middle class spaces.90 Our alternative food systems will perpetuate systemic inequality if we do not actively work to break down these barriers.

Mandela makes a point of connecting with local and regional Black farmers. “You can get okra, yams, purple hull peas, collards greens,“ says Adrionna. “Those legacy foods that we’ve been trying to reconnect our African American neighbors with for years.” The cooperative pays farmers fair prices and cultivates relationships that go beyond the current season. “More than anything, the future of our food system is planning with farmers and organizations that are working to support farmers, so that we can be consistent and prepared to sure up revenue on both ends.”

Mandela works to make fresh produce universally accessible. They participate in a state program that provides a 50 percent discount on California-grown produce for residents who use SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits. Employees also encourage customers to try new foods and recipes and connect with younger generations that may not have learned cooking skills in school or at home. Employees “engage people through their baskets,” inquiring on what they plan to cook with their purchases and encouraging them to try new things. Mandela also hosts a bimonthly online cooking show, sharing how easy and affordable it can be to cook using fresh, whole ingredients. “We are really trying to do well by our bodies,” says Adrionna. “As Black bodies are being terrorized and mangled, in overt and subtle ways, our minds are porous to manipulation; we’re doing our best to combat that and to be living examples of community healthcare and community wealth building.”

The supermarket giants built their empires by pricing out competitors. But cooperatives operate under a different paradigm altogether. “For co-ops, it’s about cooperation, not competition,” Adrionna says. “We’re focused on making a bigger pie rather than slicing and dicing it up.” For example, Mandela grew its store through a grant provided by Rainbow Grocery Cooperative in San Francisco. “Now it’s our turn to share that with the DEEP Grocery Co-op in East Oakland,” a burgeoning cooperative “whose workers are of a similar demographic, in a similarly challenged location in terms of poor health and lack of quality grocery stores.” Mandela recently provided on-the-job training for East Oakland employees and continues to serve as a resource for them on how to operate successfully.

Adrionna is confident that the worker-owned grocery cooperative model is replicable in communities beyond the Bay area. “Hopefully, the growth of the grocery co-op markets will spawn the growth of more local and independent, regionally-based companies that stick around and don’t sell out because they have more local markets that value their ethics.” Neighborhoods benefit from access to fresh, local and fairly-priced produce. Community blossoms in the interactions between farmers, workers and their customers. And worker-owners can take pride in a vocation that provides dignity and financial stability.91

“Worker co-ops are the future of food!” insists Adrionna, while stressing the need for more institutional support from governments for the cooperative model. Moreover, activists in the local food movement must work alongside communities of color that have been advancing this model for generations — not to make a white movement more diverse, but to build new food and farming systems together, where everyone has a seat at the table.

Helping new farmers thrive: Hmong American Farmers Association

In the 1970s, thousands of Hmong refugees fled the aftermath of the Vietnam War and resettled in the United States, many in Minnesota and Wisconsin.93 They brought their agricultural traditions, introducing new foods to their Midwestern neighbors. Yet Hmong American farmers found themselves in a landscape dominated by large farms with expensive machinery and inputs. They faced similar challenges in accessing land and resources as other beginning farmers, in addition to cultural and language barriers.

In 2011, a group of farm families in the Twin Cities started the Hmong American Farmers Association (HAFA)92 to create opportunities and build intergenerational wealth within the Hmong American community. HAFA provides bilingual training on not just sustainable farming practices, but also on improving business skills and creating market opportunities. The nonprofit also helps farmers access credit through state and federal agricultural programs. “Our work is a game-changer because it looks holistically at what farming families need to succeed,” said Executive Director Emeritus Pakou Hang.94

In addition, HAFA acquired 155 acres south of the Twin Cities in 2013, which is subleased in 5-acre plots to the local Hmong community. Families enter a ten-year lease on one or two plots, providing long-term stability and allowing them to plant perennial crops. The HAFA Farm also runs demonstration plots and offers access to irrigation water, composting and refrigerated trucks for hauling fresh produce. Together, HAFA Farm families grow more than a hundred different crops, the majority of which are vegetables and flowers sold in local farmers markets.

Over the past few decades, the Hmong American community has transformed Minnesota’s local food economy. Today, more than half of all farmers who sell in Twin Cities farmers markets are Hmong American. “Without Hmong farmers,” the nonprofit says, “this explosion of awareness and interest in local foods and small-scale farming in Minnesota would not be possible.”95

With farmers markets becoming saturated with local produce, HAFA is also expanding alternative marketing opportunities. HAFA helps its members sell in local community supported agriculture (CSA) shares, schools, businesses, groceries and co-ops.

HAFA is working to purchase additional land to transform into agricultural trusts for lease by the Hmong American community. Land access remains a significant barrier to beginning farmers, with one estimate suggesting it would cost more than $5 million to purchase the land and capital needed to start a 500-acre grain farm in the Midwest.96 Without access to family-held land or unlimited credit, starting a farm can be an insurmountable challenge. But nonprofits like HAFA work to overcome these obstacles while building healthy, vibrant local food economies. HAFA believes that “the best people to support Hmong farmers are Hmong farmers themselves, and that we are all lifted up when those who are affected by an unfair food system lead the change we seek.”97

Rebuilding western North Carolina’s local food economy

Tobacco was a major cash crop for much of the 20th century. But by the new millennium, it had declined in the face of global competition, changing attitudes about smoking, and the elimination of federal tobacco quotas and price supports. The federal “tobacco buyout” program provided some relief, but farmers still faced financial uncertainty, especially in economically distressed counties in western North Carolina. But with farmers so dependent on tobacco production, few alternative market opportunities existed.99

Across the region, forward-thinking leaders and community groups worked together to help tobacco farmers diversify their operations and sell into local markets. Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP)98 created the “Appalachian Grown” brand as part of a larger effort to grow the local food economy and connect farmers to consumers.100 The Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI) awarded grants funded by the state’s Tobacco Trust Fund to help farmers diversify their farms and create new markets.101 And county extension offices administered grants and held seminars on growing “everything from goats, to llamas, to cabbage, to broccoli.”102

Tobacco acreage in North Carolina’s tobacco-dependent regions dropped 95 percent from 1997 to 2012, and the total number of farms of all types dropped; however, the rate of decline following the implementation of the buyout program in 2004 was still lower compared to state and national trends.103 Thanks to the efforts of groups like ASAP and RAFI, the region’s farms diversified and reached new markets. Over roughly the same time period (2002 to 2012), the number of farms that grew fresh produce doubled, and those that sold direct to consumers more than doubled.104 An impact study of RAFI’s grant program found it helped create more than 4,100 jobs and produced an economic impact of more than $700 million in just the three years analyzed (2008 to 2011).105 Local produce production has yet to eclipse tobacco’s economic importance but “has emerged as a leading new direction for agriculture.”106

Crucial to these efforts are North Carolina’s burgeoning local food hubs. The nonprofit TRACTOR works with farmers in two western counties that previously relied on tobacco as a cash crop, and now serve as a broker between local produce farms and nearby retailers and restaurants. Farmers receive 80 cents per dollar spent on their produce — compared to the mere 15 cents the average U.S. farmer receives per food dollar — with the remaining 20 cents covering TRACTOR’s operating expenses.107 An effort led by Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture began in 2003 when its founders were told “women can’t be farmers.” The group worked to cultivate a network of women farmers and gardeners who were interested in rebuilding the local food economy. In 2016, they launched the High Country Food Hub. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the food hub served as a crucial outlet for farms that could no longer sell to restaurants.108

Western North Carolina’s tobacco transition is a case study in how a region can transition over a few years to encompass more diversified markets — if state and local leaders are willing to work with grassroots efforts and invest the resources. Similarly, contract growers locked into contracts with meat companies can transition from factory farms to smaller, pasture-based systems or diversified produce farms. Policy reform and public funding will make this happen.

Will avoiding meat and dairy save the planet?

Those of us with the resources may choose to be conscientious consumers by purchasing meat from local farms or abstaining from animal products altogether. But “voting with our forks” is not enough.116 U.S. factory farms already overproduce meat and export much of it.117 Even if everyone in the U.S. went vegan tomorrow, the industry would likely continue to produce meat. Likewise, reducing or eliminating meat consumption will not change the incentives that drive other ecologically-depleting farming systems that prop up factory farms, such as the overproduction of commodity crops on monocultures.

Moreover, animals have long played important roles in healthy, diversified farming systems, and “provide the missing element needed to develop sustainable systems, particularly in terms of soil health.”118 Integrating cattle into crop rotations can build soil organic matter and increase yields while reducing fertilizer use.119 Grazing livestock can clear fields of noxious weeds that might otherwise be killed through chemical herbicides.120 And sustainable grazing can be done on land not suitable for crop production, such as prairie grasslands, where cattle meet the ecological needs that bison once filled and help restore soil function.121 Diversification also increases a farm’s economic resiliency by not focusing on one or two products alone.122

Nevertheless, shifting to smaller, pasture-based livestock systems will ultimately reduce the amount of meat available and quite possibly raise the price of meat.123 However, many Americans are already rethinking the role of meat in their diets, with two-thirds reporting reduced consumption for health and environmental reasons.124 In fact, reducing protein intake to recommended levels by cutting back on animal products would slash per person agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. by 40 to 45 percent.125 A shift to sustainably produced, better quality meat is a win-win-win for our health, farmers and the climate.

Simply put, the forces behind what we grow and eat are too powerfully entrenched for us to “shop our way out of it.” We need to enforce our antitrust laws and overhaul farm policy — and this will only occur when we elect decision-makers not beholden to corporate agribusinesses.

Part 4:

A Roadmap For a Just Transition

Here are our policy recommendations on how to pivot to this much-needed systemic change.

Regenerative and organic farming are economically viable and already working to feed people, invest in local communities and create jobs. But federal farm policy is not designed to serve “alternative” or smaller-scale farming systems. Powerful agribusinesses have spent billions of dollars influencing lawmakers and regulators to serve their economic interests.126 But we can fight back against corporate control and reshape farm policy to achieve social and economic justice.

Enact Federal Legislation

Stop the growth of factory farms.

A handful of state legislatures have introduced factory farm moratoriums in recent years; the moment is growing. But to enact systemic change, we need a national moratorium on all new and expanding factory farms.

Models for federal legislation include the Farm System Reform Act (FSRA),127 introduced by Senator Cory Booker and Representative Ro Khanna. The FSRA would immediately ban all new large factory farms and the expansion of existing ones, and would phase out existing large factory farms by 2040.

Moreover, the FSRA would invest in a “just transition” by creating a $10 billion buy-out program for factory farm operators to pay off debt (an obstacle for farmers wishing to exit contract growing) or transition to more sustainable systems, such as pasture-based livestock or specialty crops. Notably, this funding would only be available to farmers for projects on land they own which ensures that corporate giants that created the problem do not pocket the funds.

Send a note to your Congressperson asking them to support the Farm System Reform Act today!

Stop further consolidation in the food industry.

The COVID-19 pandemic makes hitting the pause button on mega-mergers all the more critical, to ensure that agribusinesses do not use the pandemic recovery to buy out struggling competitors and further entrench market power.

Federal lawmakers are targeting agribusiness consolidation. This includes Senator Cory Booker and Representative Marc Pocan’s Food and Agribusiness Merger Moratorium and Antitrust Review Act.128 The legislation would enact a moratorium on all agribusiness and grocery mega-mergers and create a commission to recommend steps to strengthen antitrust and merger rules and enforcement. The moratorium would be in place until Congress passes comprehensive legislation to address market consolidation in the agribusiness sector.

End discrimination within USDA programs and support farmers of color.

Black farmers faced disproportionately higher rates of farmland loss throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries. This was accelerated by systemic racism within federal agencies like USDA.129

Legislation like the Justice for Black Farmers Act,130 introduced by Senators Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren and Kirsten Gillibrand, seeks to end discrimination by establishing an independent civil rights board to review reports of and appeals to civil rights complaints filed against USDA. It would also create a number of initiatives to address Black farmer land loss, including creating a land trust to provide the next generation of Black farmers with land and resources to farm.

Overhaul the Federal Farm Safety Net

The current farm safety net is just a Band-Aid on a broken system. Crop insurance provides some economic relief to farmers, but does not address overproduction, a key contributor to price slumps. And farmers are not incentivized to implement sustainable practices that make land more resilient to future disasters in a changing climate.

Reinstate federal supply management for commodities.

The first Farm Bill enacted a federal supply management program, saving countless farmers from bankruptcy during the Dust Bowl.131 The program took marginal farmland out of production and provided farmers with living wages — until it was systematically dismantled by Big Ag.132

USDA used to set a price floor for grains that achieved parity, an income that both covers the cost of production while providing farmers with a living wage. USDA provided farmers loans based on this price floor, which farmers repaid after harvest. In years when market prices dropped below the price floor, USDA collected the harvest as collateral, essentially buying surplus grains from the market for the federal grain reserve. Then when drought or other disasters reduced crop yield, USDA sold grains from the federal reserve into the market,133 smoothing out market volatility and ensuring a steady supply of grain to the benefit of both farmers and consumers.

Remarkably, supply management can operate at virtually no budgetary cost to taxpayers.134 We can reinstate supply management for grain crops and extend it to dairy, if our elected officials stand up to the corporate agribusinesses greedy for artificially-cheap commodities.

Require farmers to implement organic practices in order to participate in safety net programs.

This would provide a huge incentive for farmers to shift from ecologically-depleting monocultures to ones that incorporate cover crops, crop rotation and no-till farming. Safety net programs should also promote crop and livestock systems that are appropriate and sustainable for each region. In turn, organic practices would build soil and help make farmland more resilient to future climate change events, reducing reliance on disaster insurance.

Expand coverage for more crops that directly feed people.

Feed corn, soybeans and cotton make up a huge chunk of acreage enrolled in federal crop insurance programs,135

while many fruits, vegetables and nuts are not eligible under many programs.136 Expanding safety net coverage to more specialty crops supports farmers in shifting to new production systems and diversifying their operations.

These crucial changes will encourage organic practices and stop propping up factory farms with taxpayer-subsidized feed. However, we must also correct past failures of safety net programs to include historically underserved farmers, including farmers of color, female and beginning farmers.137

Redirect Public Funding To Support Organic And Regenerative Agriculture

Big Ag has perfected the art of funneling public dollars into maintaining industrial agriculture’s status quo.

Money earmarked for conservation programs flows to factory farms, and agribusinesses court public universities to develop patented seeds.138 It is time to end public research for private gain and instead invest in building a food system that works for every farmer, food chain worker and consumer.

Increase funding for regenerative practices.

USDA spends billions of dollars each year on agricultural research, yet only a small slice of this goes into regenerative systems.139 Federally funded research should prioritize practices that reduce chemical inputs, build soil and help farmers adapt to a changing climate. Similarly, state legislatures should follow the example of states like Maryland and California and earmark funding for regenerative practices.140

Farmers must also have access to information on regenerative practices. State extension services have long played vital roles in sharing new practices with farmers. They can be important facilitators in connecting farmers with the growing body of research on climate-friendly practices.141 We should also provide financial and technical support to help farmers — especially those historically under-served — transition to USDA Organic certified operations.

Develop climate-resilient seeds and livestock breeds and make them publicly-available.

Land-grant universities have long been incubators of new farming practices and seed varieties that were once shared widely with farmers, with each public dollar invested paying out $10 in benefits.142 But when public funding lagged, federal policies increasingly encouraged private corporations to partner with universities. Today, agribusinesses develop new seeds at public universities which they then patent. This raises seed costs and prevents farmers from seed-saving.143 Corporations are more interested in developing seeds that lock farmers into costly, poisonous pesticides than those that adapt to climate change.

Federal dollars should instead fund research into non-GMO, patent-free seeds and livestock breeds through traditional breeding methods. We must increase funding for land-grant universities and discourage so-called public-private partnerships. Seeds should be developed to respond to specific geographical conditions and to be climate-resilient. State extension services can help distribute innovative seeds and breeds to farmers and encourage farmers to save seed in order to break free from buying expensive patented seeds year after year.

Reject false solutions and close “conservation” loopholes that fund factory farms.

Money from conservation programs flows to false solutions, such as anaerobic digesters, which generate factory farm gas from manure and other waste.144 Factory farm gas is a dirty, polluting energy. 145 Digesters built with taxpayer money simply prop up factory farms and entrench fossil fuel infrastructure. Instead, we should encourage farmers to shift to smaller, integrated crop-and-livestock systems where they can sustainably recycle manure as crop fertilizer.

Another false solution peddled by corporate interests are carbon pricing schemes for farmers. Carbon pricing — or “pay-to-pollute” schemes — allow polluting industries to avoid emissions reduction by purchasing “offsets” from another source, such as a farmer who sequesters carbon in her soil. But pollution trading doesn’t meaningfully reduce carbon emissions and instead allows companies to pay to pollute.146 The practice is unfair to farmers who have already been practicing climate-friendly agriculture and are unable to claim new offsets. Instead, we must leverage existing conservation programs to implement sustainable practices and tie their adoption to safety net participation, while investing in a rapid transition to a 100 percent clean energy economy.

Part 5:

Conclusion:

We Can Build Regenerative Food Systems

This is a window into what regenerative farming systems and food hubs in the United States can look like. It is meant to start a conversation, not offer a prescription, as there is no “one-size-fits-all” model for regenerative farming. We can build new farming and food systems that work for everyone if we embrace a few core principles:

Communities of color are leaders — not afterthoughts — in rebuilding food systems.

Our great-grandparents modeled many of the farming systems and practices we strive for today, with diverse farms serving local markets. But we must not romanticize the past; our farm systems have largely benefitted white male farmers with the most capital. We need to ensure that everyone has a seat at the table, and work alongside communities of color that have been in this fight for generations. There is no food justice without racial justice.

Everyone must be able to afford to participate.

Food hubs that provide farmers and food chain workers with living wages should be accessible to everyone. In the short term, we must increase Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and extend benefits to farmers markets, co-ops and online purchasing. We must also reform labor laws to raise the minimum wage, eliminate wage theft and provide universal paid sick and family leave, so that everyone can afford healthy food.

Reform will bring choice, variety and availability.

Reforming the way we produce animal products will impact cost and availability. We can embrace a “less-is-better” approach, choosing high-quality meat, dairy and eggs produced sustainably while increasing our consumption of whole produce and grains.

Food policies must promote food sovereignty at home and abroad.

This means empowering communities to feed themselves with fresh, local, healthy food. We must also reorient our trade policies so they do not undermine the ability of farmers and rural communities in the developing world to feed themselves.147

Perhaps the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will be this generation’s “Dust Bowl” that forces a systemic overhaul. Let’s seize the moment and pressure our leaders to enact policies and make investments in food systems that work for all farmers, food chain workers and consumers.

Send a note to your Congressperson asking them to support the Farm System Reform Act today!

Endnotes

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS). “Packers and Stockyards Division: Annual Report 2018.” August 2019 at 9.

- Vogel, Stefan. “The milling industry structure in key regions—Fragmented versus consolidated markets.” Rabo-bank. June 2017. Accessed July 2020. Available at https:// research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/grains-oilseeds/ The_Milling_Industry_Structure_in_Key_Regions.html.

- Nestlé. “Our brands.” Accessed July 2020. Available at https://www.nestle.com/aboutus/overview/ourbrands.

- USDA (2019) at 9.

- CBRE. “2019 U.S. Food in Demand Series: Grocery.” May 2019 at 16.

- Sage, Jeremy L. et al. Washington State University. “Bridging the Gap: Do Farmers’ Markets Help Alleviate Impacts of Food Deserts?” Submitted to the Research on Poverty, RIDGE Center for National Food and Nutrition Assistance Research. February 2012 at 5 to 6.

- CBRE (2019) at figure 4 at 16.

- USDA (2019) at 9; Kelloway, Claire and Sarah Miller. Open Markets Institute. “Food and Power: Addressing Monopolization in America’s Food System.” March 2019 at 2 and 6.

- USDA. Economic Research Service (ERS). “Highlights from the February 2020 Farm Income Forecast.” Updated February 5, 2020.

- Mooney, Pat. ETC Group. “Blocking the Chain: Industrial Food Chain Concentration, Big Data Platforms and Food Sovereignty Solutions.” October 2018 at 8.

- MacDonald, James M. et al. USDA ERS. “Consolidation in U.S. Meatpacking.” AER-785. February 2000 at iii; Williams, Gregory D. and Kurt A. Rosentrater. Tyson Foods and USDA. “Design Considerations for the Construction and Operation of Flour Milling Facilities. Part I: Planning, Structural, and Life Safety Considerations.” Paper No. 074116. Written for presentation at the 2007 American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) Annual International Meeting. Minneapolis, Minnesota. June 17-20, 2007 at 1; USDA (2018); Willingham, Zoe and Andy Green. Center for American Progress. “A Fair Deal for Farmers: Raising Earnings and Rebalancing Power in Rural America.” May 2019 at 20 and 22; Andrews, David and Timothy J. Kautza. “Impact of Industrial Farm Animal Production on Rural Communities.” Report of the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production. 2008 at v to vii.

- Manion, Jennifer T. “Cultivating farmworker injustice: The resurgence of sharecropping.” Ohio State Law Journal. Vol. 62, Iss. 5. 2001 at abstract; Drake University, USDA Farm Service Agency and National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. “Contracting in Agriculture: Making the Right Decision.” ND at 8; Andrews, Deborah. “Traditional Agriculture, Biopiracy and Indigenous Rights.” Written for the 2nd World Sustainability Forum. November 1-30 2012 at 2.

- Liu, X. et al. “Effects of agricultural management on soil organic matter and carbon transformation — A review.” Plant, Soil and Environment. Vol. 52, No. 12. 2006 at 537 to 538; Horwath, William R. and J. G. Boswell. University of California — Davis. “How much can soil organic matter realistically be increased with cropping management in California?” Proceedings of the CA Plant and Soil Conference, 2018. Fresno, California. February 6-7, 2018 at 32.

- Prashar, Pratibha and Shachi Shah. “Impact of fertilizers and pesticides on soil microflora in agriculture.” In Licht-fouse, Eric (Ed.). (2016). Sustainable Agriculture Reviews: Volume 19. Cham: Springer at 355; Deguines, Nicolas et al. “Large-scale trade-off between agricultural intensification and crop pollination services.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Vol. 12, Iss. 4. May 2014 at abstract.

- Food & Water Watch (FWW) analysis of USDA. National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Quick Stats. Available at https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov. Accessed August 2019; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “Literature Review of Contaminants in Livestock and Poultry Manure and Implications for Water Quality.” EPA 820-R-13-002. July 2013 at 109; U.S. Census Bureau. 2013-2017 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates. Available at https://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed December 2019.

- Hollenbeck, James E. “Interaction of the role of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in Emerging Infectious Diseases (EIDS). Infection, Genetics and Evolution. Vol. 38. March 2016 at 44.

- Wing, Steve et al. “Environmental injustice in North Carolina’s hog industry.” Environmental Health Perspectives. Volume 108, No. 3. March 2000 at 229; Harun, S.M. Rafael and Yelena Ogneva-Himmelberger. “Distribution of industrial farms in the United States and socioeconomic, health, and environmental characteristics of counties.” Geography Journal. Volume 2013. 2013 at 2 and 5; Wilson, Sacoby

M. et al. “Environmental injustice and the Mississippi hog industry.” Environmental Health Perspectives. Vol. 110, Supplement 2. April 2002 at 199; Lenhardt, Julia and Yelena Ogneva-Himmelberger. “Environmental injustice in the spatial distribution of concentrated animal feeding operations in Ohio.” Environmental Justice. Vol. 6, No. 4. August 22, 2013 at 134 and 137. - Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production. “Putting Meat on the Table: Industrial Farm Animal Production in America.” 2008 at 17; Fenske, Richard A. et al. “Strategies for assessing children’s organophosphorus pesticide exposures in agricultural communities.” Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. Vol. 10. November-December 2000 at 662 to 663.

- Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production. (2008) at 23 and 25; Ribaudo, Marc O. et al. “Nitrogen sources and Gulf hypoxia: Potential for environmental credit trading.” Ecological Economics. Vol. 52, Iss. 2. January 2005 at 160; Robertson, Dale M. and David A. Saad. “Nutrient inputs to the Laurentian Great Lakes by source and watershed estimated using SPARROW watershed models.” Journal of the American Water Resources Association. Vol. 47, No. 5. October 2011 at 1025 to 1026.

- Baker, Brian P. et al. “Pesticide residues in conventional, IPM-grown and organic foods: Insights from three U.S. data sets.” Food Additives and Contaminants. Vol. 19, No. 5. May 2002 at discussion; Damgaard, Ida N. et al. “Persistent pesticides in human breast milk and cryptorchidism.” Environmental Health Perspectives. Vol. 114, No. 7. July 2006 at 1133.

- Vermeulen, Sonja J. et al. “Climate change and food systems.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources. Vol. 37. October 2012 at 198 to 199.

- Hendrickson, Mary. “Resilience in a concentrated and consolidated food system.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. Iss. 5, No. 3. November 2014 at 3 to 4.

- MacDonald et al. (2000) at iii and 12; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). “Dairy Cooperatives: Potential Implications of Consolidation and Investments in Dairy Processing to Farmers.” GAO-19-695R. September 27, 2019 at 1, 3 and 4.

- Corkery, Michael and David Yaffe-Bellany. “The food chain’s weakest link: Slaughterhouses.” New York Times. April 18, 2020; Corkery and Yaffe-Bellany. “Meat plant closures mean pigs are gassed or shot instead.” New York Times. May 14, 2020; Hendrickson, Mary. “Resilience in a concentrated and consolidated food system.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. Iss. 5, No. 3. November 2014, at 15 to 16 and 19.

- USDA ERS. Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System. “Nutrients (food energy, nutrients, and dietary components).” Updated February 1, 2015. Accessed July 2020. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system.

- Coleman-Jensen, Alisha et al. USDA ERS. “Household Food Security in the United States in 2018.” ERR-270. September 2019 at 10.

- Hendrickson (2014) at 16 to 17 and 22; Ayazi, Hossein and Elsadig Elsheikh. University of California Berkeley. Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. “The US Farm Bill: Corporate Power and Structural Racialization in the United States Food System.” October 2015 at 14 to 15 and 26 to 32.