Maybe you’ve seen a video that goes something like this: someone drinks a glass of clear water and announces that it tastes great. “Get this,” a second person says, “That came from the sewers!” The first person who sipped is shocked. “But it tastes just like tap water!” they might exclaim.

What some may know as an internet novelty is heading for our municipal water systems. Amid historic drought in the American West, several states are looking to turn sewage into drinking water.

But this is not the direction we need to go. “Toilet-to-tap” projects are very risky and expensive. Moreover, they distract from the true solutions to our water crisis: conserving the water we do have and tackling corporate water abusers.

What Exactly Is “Toilet-to-Tap”?

Already, many towns treat and reuse wastewater for purposes like watering lawns. But a small percentage are treating that wastewater and putting it back in the water supply.

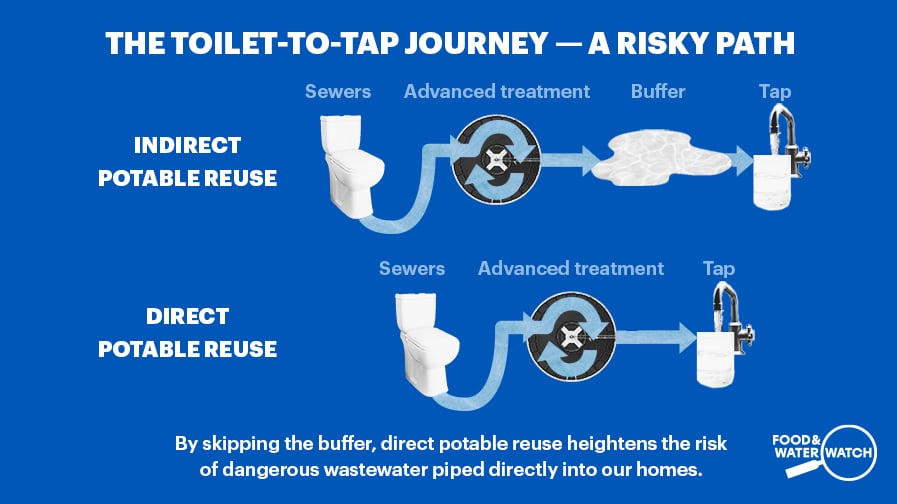

This practice, called potable reuse, starts by cleaning wastewater with advanced treatment processes. Indirect potable reuse sends the treated water into environmental waterbodies drawn on for drinking water, like aquifers or rivers. These environmental water sources create a buffer between the treatment plant and our taps.

There’s also direct potable reuse, which states like California and Colorado have set their sights on. Also called “toilet-to-tap,” direct potable reuse delivers treated wastewater directly to homes, skipping the environmental buffers.

Toilet-to-Tap Comes with Huge Hazards

Direct potable reuse projects are inherently risky. Because they lack environmental buffers, any problems in the system and in the water would quickly make their way into our homes.

Meanwhile, with buffers, systems have more time to address problems before the water travels to homes. Such problems could range from the mundane, like broken equipment and human error, to the extreme risks of illegal toxic chemical dumps and acts of terrorism.

Additionally, the advanced treatment technology used for toilet-to-tap is new, and we don’t have long-term data to help plan and lower the risks. In fact, many of the risks are potentially unquantifiable.

The technology also requires more staff and more staff training. But water systems across the country have struggled to staff their plants for normal operations. In fact, staffing problems have led to several infamous water system failures already. Adding to their burden with toilet-to-tap is a recipe for disaster.

Bottomline: Toilet-to-tap heightens the stakes if something were to go wrong. A malfunction would lead to dangerous wastewater piped directly into our homes.

Learn more about toilet-to-tap in our recent fact sheet.

Is Treated Wastewater Even Safe for Us to Drink? Doubtful.

Direct potable reuse isn’t just toilet to tap. Our sewer systems collect a variety of chemicals and contaminants from a variety of sources. Those can include

- the cleaning supplies, medicines, and soaps we pour down our household drains;

- industrial chemicals like solvents and lubricants used in factories; and

- all the muck, road salt, garbage, and more that washes down our storm drains.

Much of the research on toilet-to-tap projects focus on the risks of microbes. Companies may assure us that the water is safe from pathogens — but there is much less research on the toxic chemicals that may remain even after treatment.

Many of these toxins, including PFAS forever chemicals, are notoriously difficult to remove. Researchers have found that in addition to PFAS, contaminants like microplastics and formaldehyde remain in the water even after advanced treatment. These contaminants are linked to cancer, metabolic problems, heart disease, and more.

It’s impossible to monitor every potential toxin in a direct potable reuse system. For what toxins we do know about, many are unregulated, and we don’t know how they affect human health with low-level, long-term exposure. Moreover, many chemicals become even more dangerous when they interact with each other.

To make matters worse, these toxic chemicals can accumulate in the water over time. In direct potable reuse, the water cycles from drain to tap, over and over again, with no environmental buffer to dilute them.

Toilet-to-Tap Projects Have Serious Environmental Problems

Direct potable reuse projects often do more harm than good to the environment. While toilet-to-tap, along with other reuse schemes, is sometimes called water “recycling,” it isn’t as green as that label would suggest.

The advanced treatment systems that make reuse possible use a lot of energy. If they’re powered by fossil fuels on the grid, that means they also have a higher carbon footprint than regular water treatment.

They’re also bad for marine life. The treatment process creates toxic waste brines, which contain PFAS and other dangerous chemicals. Coastal municipalities often get rid of their brines for cheap by dumping them into the ocean, which can disrupt ecosystems and poison wildlife.

Meanwhile, in inland areas, toilet-to-tap projects can disrupt natural river flows. They take water in but don’t return it to waterways, which would lower water levels in vital rivers and streams.

We’ve already seen what happens when these levels fall, thanks to the current drought in the West. Downstream communities get less water, even if they have legal rights to the water source.

The Water Policy We Actually Need

Our water crisis isn’t just an environmental problem; it’s an equity problem. Already, millions of people in the U.S. can’t afford their water bills.

Direct potable reuse will worsen this problem, as utilities raise rates to cover the new technology. For example, in Nevada, direct potable reuse can cost up to 6.5 times higher than indirect potable reuse. Low-income households will struggle disproportionately to afford water.

At the same time, Big Ag and Big Oil have been abusing our water supplies with impunity. Every year, they’ve downed billions of gallons to expand their profits. While their neighbors watch their faucets, these two industries continue to grow and guzzle.

Not only are direct potable reuse projects risky — they distract us from the real solutions to our water problems. Governments should not be banking on toilet-to-tap and saddling low-income families with the bill. Instead, they must become better stewards of our existing water sources and rein in wasteful corporate water abusers.

The answer to our water woes isn’t toilet-to-tap — it’s stopping the water abuses of Big Ag and Big Oil. Help us spread the word!